Burnout Box Manager

What Few Racecar Drivers, Team Owners, Or Crewpersons Know About This Important Position If They Have Never Done It

by Bob Szabo

IHRA DRM - 2006 Issue #5

RACING EVENT PEOPLE: Drag racing was always a passion. As I attended the many racing events starting in the ‘60’s, the abundance of race vehicles filled my memories. Yet, racing event personnel were always present, and I often did not notice or recall their work or responsibilities. They made the events go on, sometimes with difficulty, but usually with little problem and a lot of entertainment. Then a few years ago, I became acquainted with one of the local racetrack officials who invited me to participate in running various races.

THAT CRAZY BURNOUT: My first assignment was the staging or burnout box manager. At IHRA events, that assignment is usually for racecars located from 60 feet before the burnout box to 20 feet after it. To those unfamiliar with the lingo, the burnout box is a ditch or area of the racetrack with a pool of water. Racecars drive through it or around it and back into it. Then they spin the drive tires to clean them. As the water patch thins out, the tire starts smoking. Some cars lock the front brakes and hold the car in position. The rear tires then fill the air with tire smoke. Then the driver releases the front brakes and the car goes forward a few feet spinning the drive tires. Some racecars drive through the burnout box. A few feet after the drive tires get wet, they nail the throttle and smoke the tires. That smoking gets the tires hot when the racecar screams out of the burnout box towards the starting line. Some drivers smoke them over the starting line. This burnout is a crowd favorite and has become a standard in the sport.

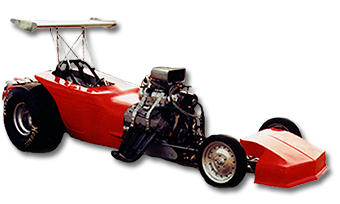

OCCASIONAL DUTY: I have had many experiences driving through the burnout box behind the wheel of my blown altered. I have also had occasional experiences with standing next to a fellow competitor’s drag race car watching that burn out. Occasionally a driver would ask me to coach a burnout. I would stand there, motioning the driver up to a location on the burnout box area where the pavement is wet. Then, when the track starter or burnout box manager approved, I would motion the driver to proceed.

BURNOUT BOX FUNDAMENTALS: The first starter I worked with was a polite associate who must have understood the insecurity from the new assignment. He said to stack them up. In racing terms, that meant to run them through as fast as possible. The trigger for directing the next pair of cars up to the burnout box was when the pair of cars on the racetrack staged on the starting line. Then when they were released and got to the half-way point, the racecars in the burnout box were signaled to start their burnout. A clinched hand signal held the cars in the burnout box. An open hand spinning the arm released the cars. After the burnout, the cars would stage at the starting line. The starter took over at that point.

BEST SEAT IN THE HOUSE: In the beginning, the starter motioned me for the timing of when to pull up the next pair. Soon I caught on to the pace. I watched every pair go down the track to the half-way point. Then I would release the next pair of cars in the burnout box. There was usually a staging manager in the staging lanes. I motioned that person to pull the next pair of drag race vehicles forward to the burnout box. People would walk up to me after their runs and ask how their cars looked going through the finish line and I realized that I never saw them after the halfway point. My pacing job focused on the next pair of racecars. It was interesting to me that here I was in a key position of viewing the racing but instead I became consumed in the task of pacing and the burnout.

SAFETY FOREMOST: The first confusion for me was getting the right cars in the correct lane. There were various rules from time to time. One was to run street-cars with street tires in only one of the lanes. Those street tires would tear up the remnant rubber on the racetrack so we kept them in only one of the lanes. I had to double check cars coming from the staging lanes to get the drag only cars with slicks on the right and the other street-cars always on the left lane. Often drivers would ignore the staging lane manager and try to sneak into a lane of choice while approaching the burnout box. That confrontation would peak with the burnout box manager who was responsible for straightening out any unauthorized lane switching.

AUTHORITY: I was soon impressed with how most of the competitors relied upon me to motion them up to the burnout box. Some ignored me and acted like they knew what to do. Occasionally my teacher, the track official, would walk up to them and say wait for your release from him (pointing to me). After a few of those, I gained confidence to manage my own responsibility and would maintain control over all of the cars, including the know-it-alls.

RESPONSIBILITY: This may seem trivial, especially to National Championship seekers, however, you have no idea what it is like to do what looks like a simple job. One common occurrence is brakeage in the starting line. Without management of the burnout box pacing, you quickly end up with racecars stacked up ahead of the box waiting for the pair on the starting line. One is broken and the event stops. I saw occasions where we had to back one or more cars out from the burnout box to make room for the broken car to be pushed out.

DANGER: Awhile back, a racecar was started in the staging lanes. Some type of accident occurred where the throttle stuck. The racecar jolted forward and hit one of the starting line crew causing serious injury. I was not there but recalled all of the times I stood in front of or behind a starting racecar. I recalled all of the times I saw crew persons and track personnel standing near the front or rear of various racecars as they started.

THE BIG PICTURE: The burnout box job responsibility became even more obvious in my mind. At the various local track events I have attended since, I often see new, young people managing that burnout box. Some have a lot more experience than I have, but some are without even my limited experiences. I see most racecar drivers and crew following their guidance. The occasional Top Eliminator wanabe’s who ignore the commands of those important track officials simply have no awareness of the events that go on around that position when those racers are off in the pits doing their own thing. Those events affect the pace and the burnout box management decisions when “Sir Top Eliminator” pulls up into the staging lanes for another world appearance.

THE RACE EVENT EXPERT: When I continued, I really enjoyed the position. Often, I would observe a car with a peculiar handling problem. As a courtesy I would advise the driver or a crewmember that was present. Many really depended on my observations. I also became aware of the track condition. Some would approach me and ask how the track was. I got better and better at predicting the condition simply from watching the racecars go down the track straight or out of shape.

MAINTENANCE MANAGER: I also soon experienced the leaker; the car that leaves a trail of fluid as it travels up to the starting line. I was the one responsible for catching that one as soon as possible to avoid a major cleanup. I quickly became aware of the oversights from some of the drivers: forgetting to buckle-up, put on the helmet, fasten the helmet, latch the hood, trunk, door, remove the hood scoop plug or cover, have a working tail light during night time racing, a tire going flat, and others. A big one was one night when a front wheel drive compact bracket street car was running about 115 mph. During his second round, I looked at his small rear tires. They were both spares; you know, the little ones rated at 55 mph max. I pulled him out from the line. The inspector who approved the car with street tires joined me in a safety instructional class for this participant. Yes, those tires are light. No, they are not safe. Then there was the fellow who left his door open and I watched him pump the brake pedal to build up brake pressure so the pedal would not go to the floor. No, you are out.

What reinforced the enforcement of all of those incidents was the many times I was called out to the racetrack to help clean up either fluids from something that broke or a racecar brush with the guard rail. After seeing wreckage from time to time, the importance of my job became even more entrenched in my mind. THE TEACHERS: Sportsman racers are often the professionals of the self-starting racecars. When I was new to the staging assignment, many an experienced sportsman racer set the pace and anticipated my command or the ones I was supposed to do. I learned fast and went on from there.

I’LL NEVER DRIVE THE SAME: Often all of the stakes are on a race, and the staging manager must try to hold the odds even for both competitors. It is a central job in the running of the race. Most of the emotion and experience I have cannot be described, but after that period in my drag racing participation, I became a more respectful driver. At an event, I would sometimes walk up to the staging manager, watch him or her, and get to know any peculiarities. But now, I know enough about that position to respect the responsibility that it has. Hats off to all of the IHRA event folks who do that job. And thanks for doing what you do.

Thanks to Skooter Peaco for editorial contributions for the burnout box management customs and policies of IHRA events relative to this article.